Image from Shutterstock (The Conversation)

Scientific publishing is not known for moving rapidly. In normal times, publishing new research can take months, if not years. Researchers prepare a first version of a paper on new findings and submit it to a journal, where it is often rejected, before being resubmitted to another journal, peer-reviewed, revised and, eventually, hopefully published.

All scientists are familiar with the process, but few love it or the time it takes. And even after all this effort – for which neither the authors, the peer reviewers, nor most journal editors, are paid – most research papers end up locked away behind expensive journal paywalls. They can only be read by those with access to funds or to institutions that can afford subscriptions.

What we can learn from SARS

The business-as-usual publishing process is poorly equipped to handle a fast-moving emergency. In the 2003 SARS outbreaks in Hong Kong and Toronto, for example, only 22% of the epidemiological studies on SARS were even submitted to journals during the outbreak. Worse, only 8% were accepted by journals and 7% published before the crisis was over.

Fortunately, SARS was contained in a few months, but perhaps it could have been contained even quicker with better sharing of research.

Fast-forward to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the situation could not be more different. A highly infectious virus spreading across the globe has made rapid sharing of research vital. In many ways, the publishing rulebook has been thrown out the window.

Read more:

The hunt for a coronavirus cure is showing how science can change for the better

Preprints and journals

In this medical emergency, the first versions of papers (preprints) are being submitted onto preprint servers such as medRxiv and bioRxiv and made openly available within a day or two of submission. These preprints (now almost 7,000 papers on just these two sites) are being downloaded millions of times throughout the world.

However, exposing scientific content to the public before it has been peer-reviewed by experts increases the risk it will be misunderstood. Researchers need to engage with the public to improve understanding of how scientific knowledge evolves and to provide ways to question scientific information constructively.

Read more:

Researchers use ‘pre-prints’ to share coronavirus results quickly. But that can backfire

Traditional journals have also changed their practices. Many have made research relating to the pandemic immediately available, although some have specified the content will be locked back up once the pandemic is over. For example, a website of freely available COVID-19 research set up by major publisher Elsevier states:

These permissions are granted for free by Elsevier for as long as the Elsevier COVID-19 resource centre remains active.

Publication at journals has also sped up, though it cannot compare with the phenomenal speed of preprint servers. Interestingly, it seems posting a preprint speeds up the peer-review process when the paper is ultimately submitted to a journal.

Open data

What else has changed in the pandemic? What has become clear is the power of aggregation of research. A notable initiative is the COVID-19 Open Research Dataset (CORD-19), a huge, freely available public dataset of research (now more than 130,000 articles) whose development was led by the US White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

Researchers can not only read this research but also reuse it, which is essential to make the most of the research. The reuse is made possible by two specific technologies: permanent unique identifiers to keep track of research papers, and machine-readable conditions (licences) on the research papers, which specify how that research can be used and reused.

These are Creative Commons licences like those that cover projects such as Wikipedia and The Conversation, and they are vital for maximising reuse. Often the reading and reuse is done now at least in a first scan by machines, and research that is not marked as being available for use and reuse may not even be seen, let alone used.

What has also become important is the need to provide access to data behind the research papers. In a fast-moving field of research not every paper receives detailed scrutiny (especially of underlying data) before publication – but making the data available ensures claims can be validated.

If the data can’t be validated, the research should be treated with extreme caution – as happened to a swiftly retracted paper about the effects of hydroxychloroquine published by The Lancet in May.

Read more:

Not just available, but also useful: we must keep pushing to improve open access to research

Overnight changes, decades in the making

While opening up research literature during the pandemic may seem to have happened virtually overnight, these changes have been decades in the making. There were systems and processes in place developed over many years that could be activated when the need arose.

The international licences were developed by the Creative Commons project, which began in 2001. Advocates have been challenging the dominance of commercial journal subscription models since the early 2000s, and open access journals and other publishing routes have been growing globally since then.

Even preprints are not new. Although more recently platforms for preprints have been growing across many disciplines, their origin is in physics back in 1991.

Lessons from the pandemic

So where does publishing go after the pandemic? As in many areas of our lives, there are some positives to take forward from what became a necessity in the pandemic.

The problem with publishing during the 2003 SARS emergency wasn’t the fault of the journals – the system was not in place then for mass, rapid open publishing. As an editor at The Lancet at the time, I vividly remember we simply could not publish or even meaningfully process every paper we received.

But now, almost 20 years later, the tools are in place and this pandemic has made a compelling case for open publishing. Though there are initiatives ongoing across the globe, there is still a lack of coordinated, long term, high-level commitment and investment, especially by governments, to support key open policies and infrastructure.

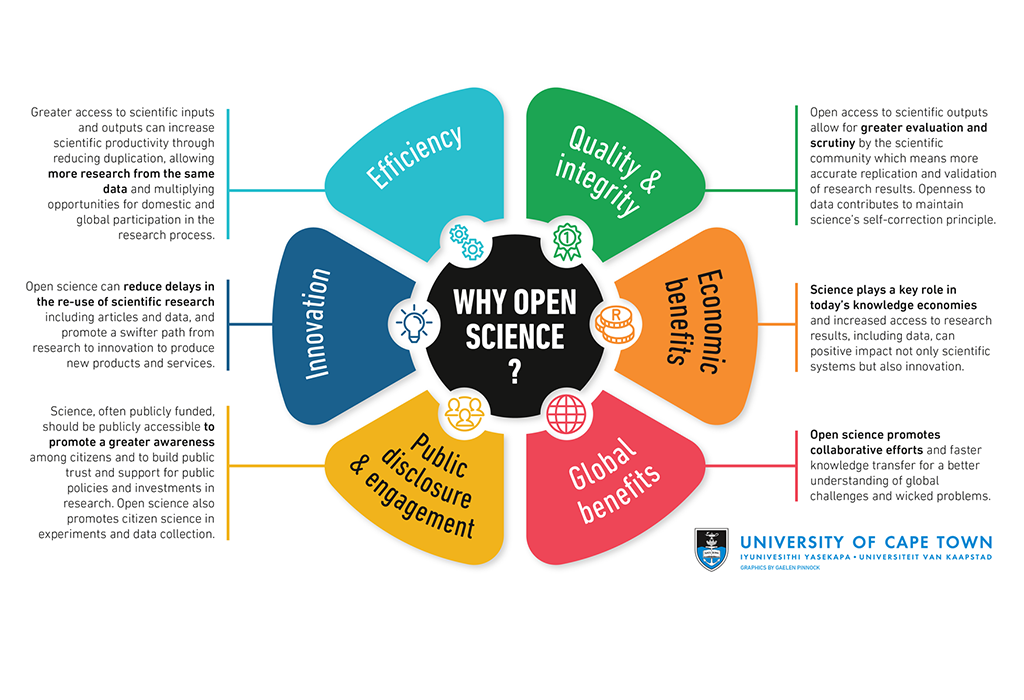

We are not out of this pandemic yet, and we know that there are even bigger challenges in the form of climate change around the corner. Making it the default that research is open so it can be built on is a crucial step to ensure we can address these problems collaboratively.

Virginia Barbour, Director, Australasian Open Access Strategy Group, Queensland University of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.